DIGA

This project about Mongrando’s Dam was born from the desire to apply some of the research methods of the Non-representative theory.

I started this research from simply hiking, a common activity for me in this area.

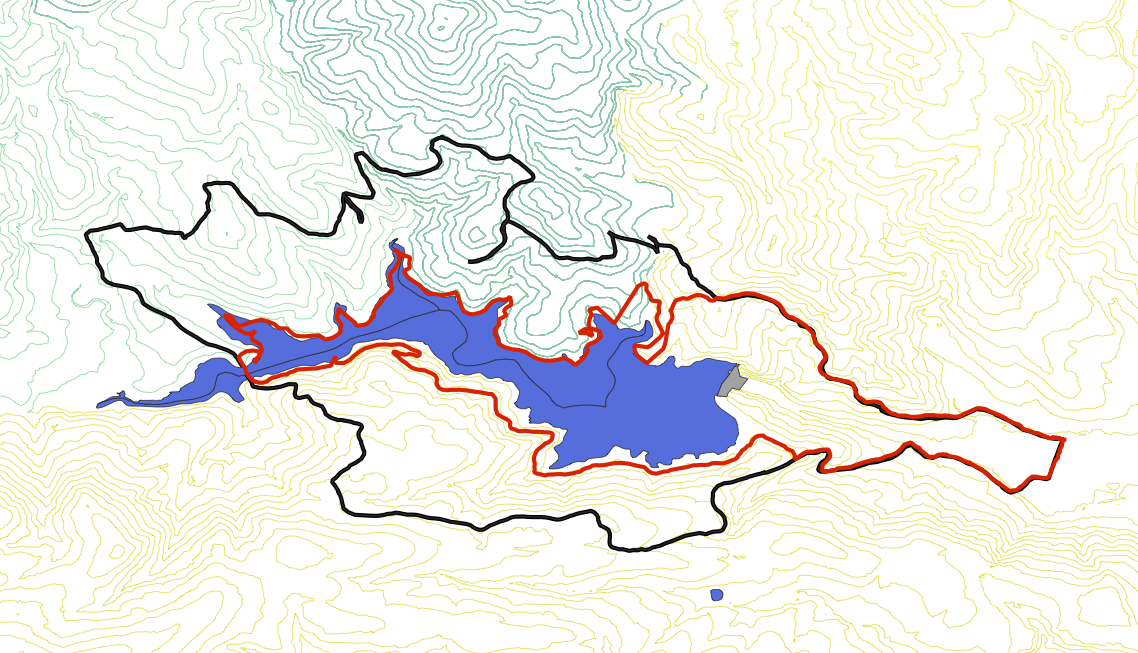

So I decided to trace what would be my survey area using a GPS device.

The result of this first approach led me to find two paths, the first one as close as possible to the water and the second one instead, closer to human activities (farms, cultivated fields, roads, etc.) that develop around the dam.

This first activity, this performed map, allowed me to start imagining how I would set up my research. Both routes were "recorded" starting from the town of Mongrando specifically from the last houses under the dam wall.

The first route, 10 km, follows the road to the Arale hamlet where I leave the road to descend on the embankment of the Dam. The first half of the route, orographic left, allows me not without difficulty to walk on the bank or not far away from it. For both routes, the bridge over the dam that connects the two banks is an obligatory passage. Right at the bridge I am forced to leave the bank of the lake, for the second part of the route, orographic right, where I am forced to follow the service road that leads to the guardian's house. The return through the woods follows closely the Ingagna river, it’s water channeled from the artificial lake towards some factories.

The second path also starts from Arale. If the first path closely followed the lake banks, in this second walk the goal is to move on the thin border that separates the forest, nature, and human activities. The route also runs for about 10km between driveways, houses, and small villages. Once I crossed the bridge the second part of the route develops mostly between paths and roads used by loggers while the way back to my starting point is identical to the first route I mapped.

If in the first route I let myself be guided by 'nature', while the second path i chose was dictated by memories, roads that have already been traced and traveled.

On the one hand, this activity allowed me to obtain borders, a (non) map, on which to set up research, on the other hand it gave way to a process of rediscovery of the territory made up of sensations, encounters, moments, memories.

The first path put me in front of a series of problems caused by the fact that the banks of the dam are mostly unreachable and impassable, only in some points where the banks become accessible the journey becomes more agile and you can meet some fishermen or their tracks. Proceeding on the orographic left side is therefore often difficult, you have to wade through some streams, climb up rocks and steep slopes. As I approach the bridge the scenery changes, continuing on the service road, a few meters of vegetation separate it from the water but the outlines of the Diga already seem to be confused, hiding. As the trail ends I take the service road that leads me to the guardian's house. From here you can easily reach the shore and you can admire both the wall that contains about 8 million cubic meters of water in which the Mombarone and the surrounding nature reflect.

The second route is significantly easier, you can switch between dirt and asphalt roads, trails marked by hikers and houses that I imagine as the last outposts before that stretch of water that meets my gaze once I cross the bridge. After the bridge the dam gets hidden by the surrounding nature and I will loose sight of it as I go up the paths and roads created by the woodcutters.

The feeling after these two excursions is to be faced with a non-place, in the sense of a place not perceived and not defined by those who live within (or just outside) the boundaries I have drawn. A ‘margara’ who spent her entire life a few hundred meters from the reservoir asked me how to reach the bridge, even though I grew up at the foot of this wall, I had no idea what the banks were like and how they could be reached.

Loss and indefinability.

The second phase of collecting materials begins with these sensations. The studies by Vannini and Lorimer have been of great help in choosing the next steps: 'I have found immense value in a non-representational approach that seeks to' evoke rather than just report '(Vannini, 2014, p. 318) 'and draw attention to the 'background hum' of everyday experiences (Lorimer, 2008, p. 556).

Having taken the first step, it was a question of finding a way to bring the aforementioned concept of ‘evoke rather than just report’ into this research.

What follows is an evaluation of the different approaches I could have taken to describe but not represent this place or non-place.

Thus began a series of days dedicated to the exploration of the territory and the search for the right means and media to use including audio recordings, videos, photos, drawings and writings.

The research process leads me to focus more and more on the collection of audio and video material, bringing with it a whole series of issues relating to the use of this material which, from the first review, highlights the risk of being too representative.

A study by Kaya Barry entitled 'Circadian Rhythms, Sunsets, and Non-Representational Practices of Time-Lapse Photography', published in Candice Boyd's book entitled ‘Non-Representational Theory and the Creative Arts’ gives me a series of insights and ideas to carry out the research from a visual point of view.

After several attempts, the choice falls on the use of artificial intelligence, an approach that allows me to return to my feeling of being in front of a non-place where boundaries are lost and confused, where everything is variable and man and nature become contaminated with the dam as the only limit. The output is a video in which images and sound merge without giving reference points, letting the emotions tell themselves.

The video, made in collaboration with Anna Leda Perinotto and Leonardo Tanzi, was created by 'feeding' the AI 120 photos taken during the days of exploration of the area in which natural and anthropogenic elements alternate. The GANS, as this technology is called, processes the images trying to reproduce an output image as similar as possible to those given as input. In this case, since the images are very different from each other, an effect is created whereby the elements mix without ever reaching a representative image but a video, which in my opinion is very evocative and an exact translation of the sensations experienced.

On a sound level, I personally treated and selected some extracts from the over two hours of audio material collected.

Alongside this A / V process there is the writing of a short text that has the same objective, in which written sentences alternate along the two paths, a dualism that leads to a single question: Where's the Diga?

This first phase of study and research therefore produced three outputs: a performed map, essential for moving physically and mentally within the survey area; a video that aims to give back to those who will read this research the sensation, the feelings, which I felt by moving to the intent of space, a purpose that it shares with the latest output: the text.

a non-representative research

Diga hides protected by nature/Where’s Diga?/The caretaker’s house/The mill/A new landscape/A road full of memories/Improvised footpaths/Follow the roads/Human intervention/Human abandonment/Where’s the water going?/Where’s the water?/A fisherman/A farmer/Climbing/Smoking/The Bridge/The Bridge/Fishermans/Deer/Birds/Tractor/Silence/Noise/Fisherman’s house/A sweet memory/Rice?/Chestnuts

Diga is over our heads

Why? Why?

Do you know that?

No! No? Yes! Yes?

Where’s the water going?

Drink it. Rice. Fire.

Who owns the water?

Drink it Rice Fire

A virus A connection with the world

Diga hides protected by nature.

Where’s the diga?

What's next?

Where's the Diga?

The first phase of the research thus brings to light a series of sensations and reasonings that are summarized in a question: Where's the Diga?

We are faced with a human construction that has very little dialogue with the population that overlooks it, as shown by the case of the ‘margara’who wonders how to reach its shores.

Certainly there is an indirect influence dictated by the changes of the ecosystem that this infrastructure operates on the landscape, an interaction that becomes tangible, for example, by observing the fishermen who reach the reservoir preferring it to the part of the previous stream, clearly less fishy.

In recent years this reservoir has been at the center of a debate triggered by the will of the construction consortium of the dam which intends to divert part of the Elvo River, through a tunnel that would cross the entire valley, to make it flow into the dam. The purpose of this deviation, strongly criticized and for now abandoned, is to increase the water capacity of the man made lake.

Work that would not have added any kind of value to the dam, however, impacting heavily on the landscape and the ecosystem.

So we talk about Diga but we don't live it. A hypothetical danger for the people that live under the wall, a place to fish for others, a place to run or take a walk for a few.

Where's the Diga? Because it hides, a presence that rests hidden by nature but which is not natural.

Several times in the course of this research I have wondered how the use of this place could change. Does it make sense to imagine discovering the dam, 'breaking down' this wall that separates it from the valley?

Does it make sense to imagine this place as a direct economic resource for the valley? Whether it is dictated by tourism or due to the exploitation of the structure itself.

These are complex and perhaps useless questions, a game of possible scenarios that I believe, however, is worth putting into action.

This research does not bring with it answers but questions, it does not end but lays the foundations for a more complex reasoning on the perception of this area and its future.

In the text created by contrasting the notes collected during the two paths to Where's the Diga? There is a second question: Where's the water going?

If on the one hand this research was born with the aim of not representing this area and opening a discussion about it, on the other hand it is natural to ask ourselves where this water goes and why.

If historically the Ingagna stream has been the engine of forges and factories, now certainly the same cannot be said. This reservoir was born in the 90s by the hand of the Baraggia consortium. The main purpose of this basin is to provide constant irrigation to the rice fields of the lower Biella and Vercelli areas.

This is not the only function it performs, part of the water is fed into the water network as well as being used as a support point by Canadair in the event of a fire in the surrounding areas.

The water collects unnaturally before going to perform its tasks. Who benefits? Who has profits in this movement?

During these weeks of research I found in the definition of 'Hinterland' given by Brenner and Katsikis 'Operational Landscape' an interesting point of view to try to reason on this last question: 'The term 'hinterland' is used here to demarcate the variegated non-city spaces that are swept into the maelstrom of urbanization, whetheras supply zones, impact zones, sacrifice zones, logistics corridors or otherwise.'

My reasoning on the Dam was born by analyzing the latter as an entity confined to a specific space, without taking into consideration the influence it exerts beyond the wall.

The Diga, as mentioned, is not perceived or scarcely considered by the inhabitants of the valley, but how important is this 'supply zone' for rice producers? And again, letting your mind run wild, this fine rice, dressed with a thousand certificates, is sold in how many restaurants and supermarkets around the world?

The profits generated by the Dam are 50km away from it at best.

The water then flows and activates an industrial production, leaving aside the 'virtuous' use that is made of it , what will happen to the Diga when water is no longer needed?

For some time there has been talk of eliminating the use of the attachment technique of rice fields in favor of dry cultivation in the coming years. The problem of climate change is added to this perspective. Less and less snow falls on the mountains of the Biella pre-Alps, how long will the Ingagna stream have the strength to fill this basin?

As said, this research does not bring home answers but opens up questions and it comes naturally to me to go back to the one written a few lines above: it is necessary to open a discussion, a reasoning extended to the population on what the future will be. If flowing water brings profit and benefit to people potentially all over the world, what happens when it is no longer useful to the production machine?

One last, banal question before going on with this research: